CULTURE WAR

by Len Wallace

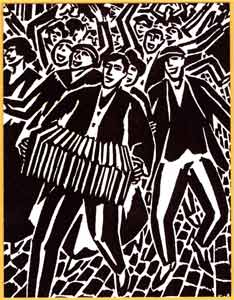

Allow me to be as passionate as when I am singing to a workers' picket line. Aside from some formal nods and acknowledgment, how is it that working class organisations, organisations of the political Left, the "movement" have failed to develop and utilize its most powerful political weapons? I am speaking of culture and cultural methods of struggle.

I have been told that in times of profound economic crisis as global capitalism restructures itself without care to the lives it shatters, culture is of little matter or interest: "Doesn't appear to be much interest in workers' culture, even amongst workers themselves." How shortsighted!

As Morris Dickstein wrote that cultural history is often viewed as "soft history" (Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression). Neither is it "soft politics", secondary to "real politics" and "real struggle". To separate the cultural from the political and economic is a mechanical materialism that turns flesh and blood human beings, the active Subject, with thoughts, dreams, ideas, voice, hopes, judgments into categories of abstract labour simply responding to capital. The failure to recognize the cultural in its multiplicity of forms as intrinsic limits the content of struggle.

Theodor Adorno, so influenced by Hegel and Marx's dialectic, so shattered with the mass butchery of the nazi death camps concluded that commodity society has drugged us. Our search for freedom limited because we are "planned in as consumers from the outset" and "reduced to the status of functions." (History and Freedom). It would be foolish to ignore this magnificently pessimistic insight as long as we do not give in to it.

We spend half our lives at work. How we work, where we work, has decisive impact. We respond to this condition in ways that are cultural. We develop ways and means to give meaning to our lack of control and to the conditions of our lives in a poetry of thought and action. Why is it that working class organisations, trade unions, organisations of the political Left cannot recognize the power of culture when corporate and State power surely have since the dawn of capitalism?

Witness the attempts to silence dissident cultural voices. Those blacklisted - Agnes 'Sis' Cunningham, Paul Robeson, or tortured and murdered - Chile's Victor Jara, South Africa's Mini Vuyisile. One way to destroy the resistance of a people is by stealing, subverting and abolishing their culture. In the West Indies colonial masters tried desperately to eliminate the use of native drums. England's political elite attempted to ban the use of Gaelic, forbade the use of bagpipes in Scotland. suppressed the stepdancing of native Irish. In the 1930s Hitler's nazis tried in vain to eliminate jazz music. In Brazil the military and clergy mounted campaigns against that devilishly suggestive working class dance, the tango.

It could be done in part by taking away cultural free space. Cases in point during World War II, the Savoy and other theatres, centres for jazz culture, were closed because of the intermingling of blacks and whites that challenged Jim Crow. The Canadian government's forced closure of the Ukrainian Labour and Farmer Temples. Such ethnic (often Russian, Ukrainian, East European) halls built in the period after World War I functioned as centres for free discussion amongst a disadvantaged immigrant urban working class that was to become the backbone of industrial unionism. They were a far cry from the later government supported organisations meant to integrate into the status quo under the banner of a false liberal multiculturalism.

While we may be born into an imposed system, slotted into place we do not own or control we respond culturally to survive in a constant struggle to reappropriate meaning in meaningless labour and to gain some vestige of control over our capacities and needs as human beings. We respond to our work conditions and the conditions of our lives as a result of work in a poetry of thought and action. As historian E.P. Thompson noted social class is not just a thing. It is a relationship of one group of people to another with opposed interests. It is in cultural ways that a class identifies and becomes conscious of itself.

Culture is fluid and lies at the critical juncture of the identities of social class, national background, ethnicity, colour, gender. Culture can be used to blind, mystify and fill in the cracks in the system, but it can also advance critical consciousness of predominant values and create space for free thought.

Song and poetry, for instance, carry as much political force as any manifesto and often far more enduring, incendiary and communicable to the collective. The IWW's Joe Hill "pie in the sky" became a part of working class and popular culture lexicon. Hill's song targeted religious proselytizers of the Salvation Army (aka "Starvation Army) who denounced earthly rebellions as wicked. The union contended for the hearts and minds of the great impoverished working class with streetcorner soapbox speeches and songs urging workers not only workers to demand their share but "the whole damn pie". In 1912 twenty thousand mill workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts went on strike. Young women carrying a sign demanding "Bread and Roses" inspired James Oppenheim's poem declaring "Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew. Yes it is bread we fight fore, but we fight for roses too!", an emancipatory message that later was adopted by the women's movement. Precisely! Our struggle is more than about bread!

Cultural expression extends to clothing, fashion, style with political meaning and ramifications. The banning of the wearing of kilts in Scotland after the failure of the last Jacobite rebellion in 1745 perhaps finds its historical corollary the stigmatization and repression in the 1940s of the "zoot suit" with its wide padded shoulders, ankle tapered trousers, long chain, double wide brimmed hat. Stuart Cosgrove reminds us that fashion was a way of "negotiating identity" for working class Black and Chicano men. Considered a moral affront to white American patriotism following government imposed restrictions during World War 2. ("The Zoot Suit and Style Warfare") gangs of servicemen beat up zoot suiters on the streets. The racial/class tension burst open in zoot suit riots of 1943 from Detroit to Harlem to Los Angeles and made a profound impression on zoot suiters such as Cesar Chavez and Malcolm X.

Forward history to the 1980s and its equivalent is the "gangsta" look predominant in the culture of hip-hop and rap, from the too baggy pants to the wearing of oversized baseball caps askew on one's head. The fashion signifies an identity of class and colour. The gangsta look (along with the rap and hip hop music) becomes commodified by an ever resilient capitalism and sold to suburban white kids.

Cultural/political meanings can change. Sometimes they are lost. Today no one gives second thought to a greeting such as "Hey, man!" which had deep meaning to Black jazz working musicians such as Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie confronting a system of Jim Crow racism in which Black men were referred to as "boys". Jazz culture of music, style and creative use of language had its political implications with this demand for self-recognition and dignity.

Ma Rainey sang in "Misery Blues":

I've got to go to work now,

Get another start,

Work is the thing that's breaking my heart,

So I've got those mean ol' misery blues.

And work is indeed a misery. The nazis proclaimed a horrendous lie when they raised up the slogan of "Arbeit Macht Frei" (Work Shall Make You Free) at Auschwitz. Yet is not that the very essence of what is taught to each one of us today? Entering the gates of the workplace is often like entering the gates of Dante's Hell - "Abandon all hope ye who enter!" Capital demands that we subject our physical beings and minds to the drudgery of work. Unfortunately for capital, our minds, our ideas (and thus culture) cannot be completely controlled.

Jazz musician Wynton Marsalis (Moving to Higher Ground) makes the important point that "art forms actualize the collective wisdom of a people. They represent our highest aspirations and our everyday ways, our concept of romance and our relationship to spiritual matters, as well as how we deal with birth, death, and everything in between. In short, the arts focus our identity and expand our awareness of the possible. . . That's why art is an important barometer of identity." To which Bertold Brecht would have added, it is a tool to shape the world.

Adorno held that in the era of capitalism the listener of music is converted into "the acquiescent purchaser" of a marketable commodity meant to sell other commodities. ("On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening"). Partially correct, but workers appropriate meaning even from commercialized pop music genres. How many of us have not identified with Johnny Paycheck's "Take this Job and Shove It!"? Dolly Parton's "Working Nine to Five" asserted "what a way to make a living!" Randy Bachman's "Takin' Carte of Business" when you "get up every mornin" so that you "start your slaving job to get your pay."

Little did Todd Rundgren know that "Bang on the Drum", casting working as lazy - "I don't want to work. I just want to bang on the drum all day!"- would be given a different meaning by workers who saw it as the desire to escape the mindlessness of assembly line work.

A young Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels recognized that the dominant ideas of a society are the ideas of the dominant ruling class. Music, jokes, language, dance, poetry can indeed echo the dominant ruling ideology. But because these very things are created by human beings, and because capitalism is not a condition of human nature and history has not come to an end (contrary to what neo-liberal social Darwinists would have us believe) it can move from irreverence to defiance, rebellion, to new possibilities and a freedom that goes beyond the restrictive limits of capital. Like the grandfather in Clifford Oddets' "Awake and Sing", we too can shout that life need not be written on the back of a dollar bill.

Small rebellions of the apparently mundane can signify real human struggles for recognition and self-valuation. For centuries old practice of carpenters secreted away small notes with their names inside the walls of the homes they built. Autoworkers would write their name within the panels of vehicles to mark "I helped to build this car". Stonemasons carved their own likenesses into the faces of the gargoyles on Ottawa's parliament buildings. Woodcarvers carved their images as the faces of the saints in the pews of Montreal's St. Jean Baptiste church.

These instances are not that far removed from the graffiti we see on the sides of railway and subway cars. When those spontaneous acts of art (and no less art because of their immediacy) first appeared they were perceived as damage to property and mindless acts of vandalism. They were more than that. They were commentary on a society that offers urban working class youth no recognition and no future. Those youth affirmed, "This is the sign that I exist, I AM".

Culture does not exist in the abstract or societal vacuum There is a class culture, a labour culture. It is our culture. Then there is their culture - that culture that wishes to shape our minds to keep us in our place, to accept our status and preserve the status quo.

There is a great lesson to be learned in the way the way the Industrial Workers of the World preached the "gospel of discontent" as one old Wobbly put it. They were adept at utilizing the cultural factors of music, poetry, song, jokes, cartoons, stories, symbols, not only as weapons in particular struggles but as a method of self-emancipation. Their newspapers were open to a workers openly encouraged to develop those creative abilities. If the union was about building a democratic institution and a better world, then creative expression from the bottom up had to be encouraged. The IWW built a culture of defiance. As folklorist Bruce Utah Phillips noted, ordinary workers like Joe Hill (and so many others) defined the conditions of their work and defined a solution to their problems. This was not culture imposed from above nor made "for" them.

One can point to the freedom struggle against apartheid in South Africa. Could it have rallied the collective, empowered the key element of the working class, if cultural methods of struggle were not encouraged, developed, promoted and sustained? A movement that does not sing, dance, tells its story, develops its language or art and cannot create a poetry of action and the action of poetry is a movement without power.

It is much too easy to dismiss culture as a "thing" that is of little importance in the climate of economic depression when workers and working class organisations have been increasingly put on the defensive. The cultural weapon allows us to redefine and seek new possibilities that ultimately empowers the collective to think beyond the limits of capital. Without these weapons there is no movement in "the movement". As singer, songwriter Steve Earle sang it:

Yeah, the revolution starts now

in your own backyard

in your own home town.

Whatcha doin' standing around?

Just follow your heart

the revolution starts now."

Len Wallace homepage